The technology developed by researchers from the Water Systems and Technology Institute at the Faculty of Natural Sciences and Engineering, Riga Technical University (RTU), enables the breakdown of biomass and other substrates in a much shorter time without the use of chemicals, producing sugar that, once purified, can be used for the production of various market-demanded products.

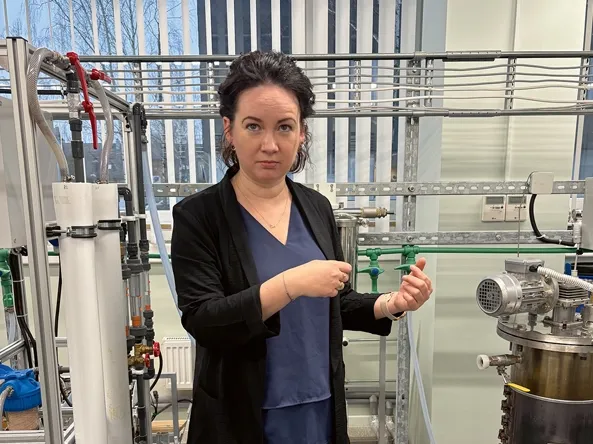

It is used to separate the undivided particles from the sugar solution. Photo: Uldis Graudiņš / Latvijas Mediji

Recycling, not rotting and polluting

Various agricultural and green waste can be quite a challenge due to the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions they create and the pollution they cause. Researchers have started with natural meadow grass. After mowing, it needs to be harvested. What should be done with it? Not all meadows can be grazed, and not all grass is used. Recyclable biomass also grows abundantly in cities by autumn—leaves and other green waste. Forest industry leftovers, including branches and tree tops, are also biomass. In scientific terms, biomass is anything that contains cellulose and lignocellulose, the main component of which is sugar.

In an EU project implemented several years ago by researchers at the Water Systems and Technology Institute, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Engineering, RTU, a technology was created that allows the effective treatment of grass and agricultural waste biomass much faster using natural means – enzymes produced by fungi. This process makes it possible to produce sugar, which can be used to make demanded products and biogas.

As the institute points out, the project's deeper purpose is to utilize the unnecessary parts of biomass. Instead of leaving it on the ground in piles, the usable part is removed.

The institute emphasizes that the project, during which a membrane technology was also patented, aligns with the European Union's Renewable Energy Directive.

Namely, energy production should use alternative substrates, not agricultural crops. For example, corn is a very good raw material for biogas production. According to the Rural Support Service, the areas of corn grown for biogas production by the five largest farms exceeded 527 hectares last year. The most – 239 hectares – were cultivated by Jānis Vintera's farm "Līgo" in Lielplatone Parish.

RTU researchers primarily focused on sugars or carbohydrates. Enzymes obtained from fungi break down biomass and green waste. In the next phase, sugar and lignocellulose are collected. Cellulose mainly consists of glucose molecules. The sugar can be used as food for bacteria, which can then be used to produce other products. Biogas can also be produced from more easily degradable substrates.

During the project, researchers also investigated which fungi produce the most enzymes, and these enzymes need to be collected.

Sugar extraction process

"By adding the right fungal enzymes to the biomass and combining them in the right proportions, we accelerate the biomass breakdown process. It doesn't take months – the breakdown, fragmentation, and sugar extraction successfully occur within a week. To clarify, we obtain a mixture of various sugars, not regular table sugar. The solution of different sugars is not pure glucose. There will be two glucose molecules together – disaccharides, also something from fructose, xylos, and other carbohydrates. We have also tried to separate them, but the separation is currently unconvincing," explains Dr. sc. ing. Linda Mežule, Director of the Water Systems and Biotechnology Institute, Faculty of Natural Sciences, RTU.

How can sugar be successfully obtained from biomass, which could then be used in fermentation processes? Mežule states that researchers initially worked more on ethanol production. "As daily needs and requirements evolve, the cost-effectiveness isn't as great. Then, more valuable products are considered. This sugar solution can be adapted everywhere glucose is needed for fermentation. This can include citric acid, bioplastics, or other microbiological products," continues Associate Professor L. Mežule.

She emphasizes that one of the key benefits of the project is the discovery of specific fungal cultures capable of producing large amounts of effective enzymes. These can be used in hydrolysis processes. RTU researchers have demonstrated that with the enzyme technology they developed, various substrates and waste products, not just biomass, can be processed. This means they can be broken down using biological methods, not chemicals. The deeper purpose is to use the unnecessary parts of biomass.

The biggest challenge – enzyme extraction

L. Mežule emphasizes that in the project, the most important aspect was how fungi can be used to obtain enzymes. Thus, the use of fungi was an essential condition for the project implementation. Nowadays, many people grow fungi at home. There is also a trend to make products from fungal mycelium.

In nature, lignocellulose is only broken down in the forest. At the Water Systems and Technology Institute, these fungi are grown in the laboratory. In a favorable environment, fungi produce enzymes. These are collected and used to break down biomass.

Enzymes can be purchased from sellers in other countries. L. Mežule states that these are additional costs, and the buyer becomes dependent on specific products. "For this reason, we mainly used fungi collected from forests. We selected and evaluated how actively they produce enzymes. The best example of enzyme production is polypores. There are different types of them, some of which break down wood very effectively. Essentially, the green part is also in there, along with other substrates. The biggest problem is that the material is heterogeneous, with both harder and easier-to-break-down fractions. The best is the first spring grass. However, no one collects it much! When coniferous tree remnants come, there is resin involved, which is not ideal. Similarly, various impurities," reveals L. Mežule.

Several fungal cultures were purchased from collections in other countries. "If it was known that fungi produce enzymes, we purchased five strains and evaluated which were most suitable. Of course, we know that we need to look for fungi that degrade wood.

The fungi that produce the required enzymes had their species identified, and we sent them to other countries for genetic analysis. We do not maintain our own fungal collections. During the enzyme extraction process, we concluded that freshly collected fungi from the forest are much more effective and produce better results than the tired laboratory cultures. It seems that one species, however, has different strains that produce enzymes differently.

These are also different in terms of biomass breakdown ability. Our most important product was enzymes from various fungi found in nature.

We need to encourage them to produce enzymes! It's not as simple as taking a fungus, a polypore, and having the enzyme flow out. In our laboratory conditions, we had to create the necessary conditions to make the fungus want to produce them," says L. Mežule.

She explains that first, the fungi are provided with favorable conditions for growth with substrates and nutrients. Then, gradually, the nutrients needed for enzyme production are introduced.